In which we discover that everything is not always as it seems, that you should take advice from helpful travellers, that bees can be excellent as a home protection system and that the taste of honey can make you cross worlds.

In which we discover that everything is not always as it seems, that you should take advice from helpful travellers, that bees can be excellent as a home protection system and that the taste of honey can make you cross worlds.

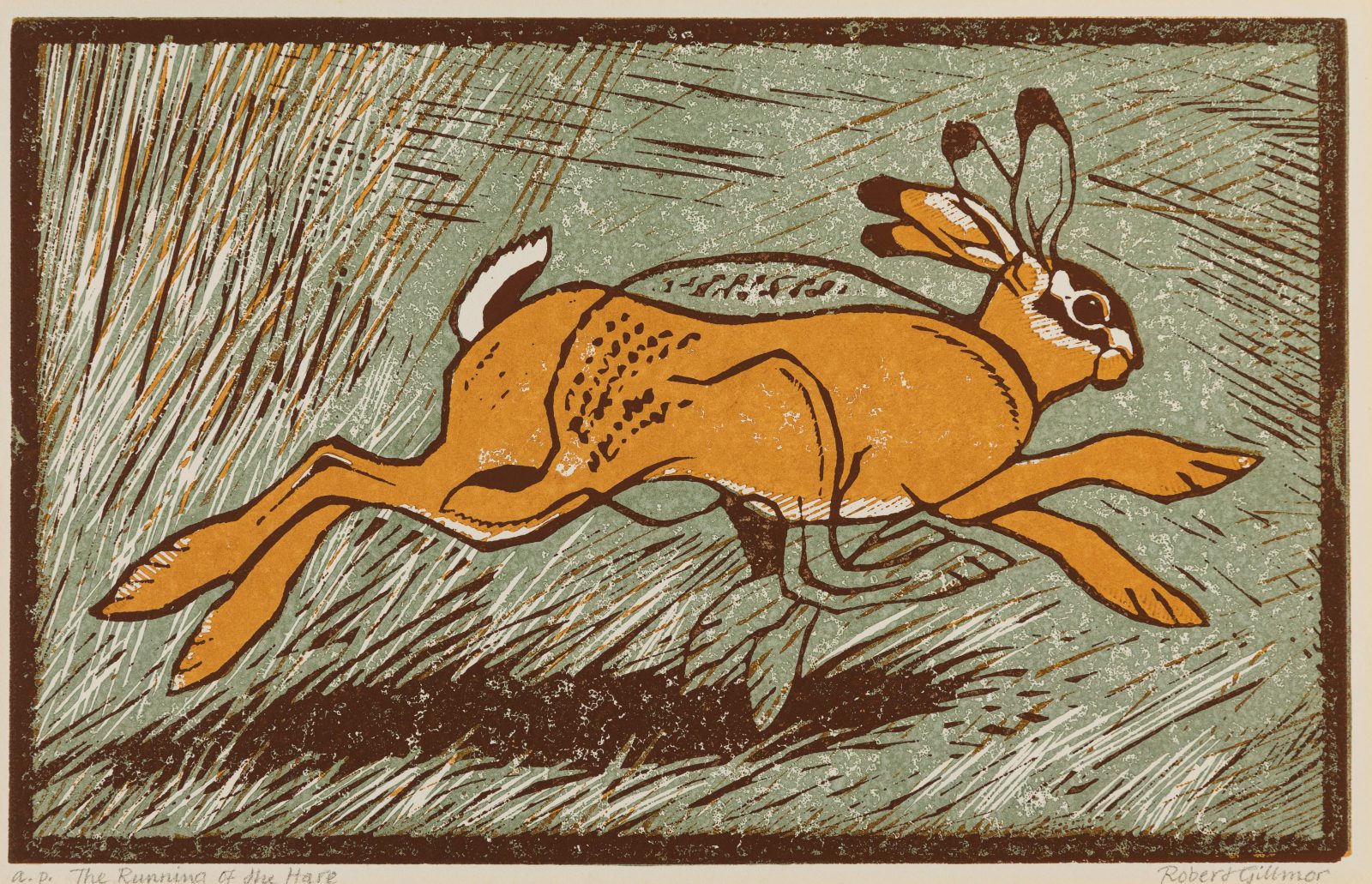

The Story: The Beekeeper & The Hare adapted from Thistle & Thyme collected by Sorche nic Leodhas

The Recipe: Hot Honey

If you would like to find out more about what I talked about in this episode you can find books and links at Further Reading

You can find more about me and Folklore, Food and Fairytales via my Linktree

You can find the interviews in my newest interview series here: How Food Frames Stories. You can find my interviews with storytellers here: Vernacular Voices of the Storyteller

You can also subscribe here (or just read) my free newsletter for further snippets of folklore, history, stories, vintage recipes, herblore & the

occasional cocktail.

You can also find out more at Hestia's Kitchen which has all past episodes and the connected recipes on the blog.

So, what did you think of the story? I absolutely loved it, perhaps I should have kept it for All Hallow’s Eve but I felt it was the perfect story for this 3rd birthday episode and this will also give you a chance to tell it as part of your celebrations should you do that sort of thing. This is a story from the highlands and has some interesting elements which are not regularly found in folktales.

Firstly the bewitched hare: the symbolism of the hare has taken part in many rituals, christian or otherwise down through the years. Hares were associated with the moon, goddesses, messengers of goddesses, as tricksters as well as symbols of fertility and temptation. Hares were even given ritual burials alongside humans during the Neolithic age in Europe. Archaeologists have interpreted this as a religious ritual, with hares representing rebirth. Over a thousand years later, during the Iron Age, ritual burials for hares were even more common, and in 51 B.C., Julius Caesar mentions that in Britain, hares were not eaten, due to their religious significance. As we have so little non Roman documentation of this period of history in these islands we may have to look at this with a dose of healthy scepticism but it does give us and indication that hares were special.

There is also very strong connection between hares and witchcraft, particularly in Northern Europe during the Early modern period. Witches were often believed to be able to take the form of hares and there are many tales of hunters chasing hares who managed to escape into homes and when the hunters enter the house, the only being available is the suspected witch in her human form with no sign of the hare. In darker tales, a paw was chopped off the hare and a suspected woman would be found with her hand chopped off at the wrist. Sometimes the witch in the form of the hare would be suspected of stealing milk or crops, other times accused of running errands for the devil. This actually appeared in the transcript of a forced ‘confession’ during the period of the witch trials.

What makes our story a little different is that the young woman was bespelled into a hare by a witch instead of being a witch who could shape shift herself. There are other stories where people are transformed into animals by witches but these are often in the form of curses such as the tale of The Princess of Cats where a whole kingdom is cursed.

The second unusual element in the tale is the beekeeper’s consideration for travellers and the travellers connection to magic being benign and helpful to the hero of the tale, providing him with guidance which allows him to marry his love and overcome the enemy witch with help of the bees. This is sadly not always the case in tales. The original in this case uses the term Gypsy as well as Traveller but as it is often now considered a perjorative term, I changed all references to Travellers as it is highly likely that a Traveller in the Highlands of Scotland woudl have been a Scottish Traveller rather than Romani.

Bees are laden with folklore and although not known usually as a traditional cause of death, they do have strong connections to death and the underworld. In pre Roman Britain it was believed by some that bees could carry messages from our world plane to the world of the dead and could bring back messages from the Gods in the Otherworld so bees were treated with much respect.

Some even considered bees to be the reincarnated souls of the dead whilst others thought that a person’s soul could leave their body in the form of a bee during a trance or deep sleep. There is a tale from Lincolnshire which relates that two travellers to the city lay down side by side to rest, and one fell asleep. The other, seeing a bee settle on a neighbouring wall and go into a little hole, put his staff into the hole and so imprisoned the bee. Wishing to pursue his journey, he endeavoured to awake his companion, but was unable to do so until he removed his staff from the hole with the result that the escaped bee flew to the sleeping man, and went into his ear. His companion then woke him, remarking how soundly he had been sleeping, and asked him what he had been dreaming of. “Oh,” said he, “I dreamt you shut me up in a dark cave, and I could not wake till you let me out.”

This is an English tale but this was a belief across the old Norse world, so much so that they even had a special word: ‘hamfarir’ for these wanderings of the soul of a living person. I love this idea, maybe some people’s vivid dreams could be said to be due their soul’s travelling. Although on consideration, it is also terrifying, especially when you consider how vulnerable a bee is to carry such valuable cargo. I will definitely continue to feed any exhausted bees I encounter with sugar water just in case another soul is on board.

Some even consider the English Tradition of telling the bees about the death of the head of the household originates from the belief that they were men’s souls, and if not informed about the new master they would fly off to heaven to seek for the old one. We don’t however have a definitive source for this although the actual need to inform the bees was taken seriously, and sometimes hives would even be swathed in black crepe during the period of mourning.

There are several witnessed incidences of Telling the Bees: ,

At Stallingborough, in Lincolnshire, about 1840, a few days after the death of a cottager, a woman staying with the bereaved family asked the widow, “Have the bees been told?” The reply being in the negative, she at once took some spice cake and some sugar in a dish and placed the sweets before the hives, then rattling a bunch of keys repeated this formula:

“Honey bees, honey bees, hear what I say!

County Folklore, vol. v, Lincolnshire, 1908

Your Master J. A. has passed away.

But his wife now begs you will freely stay, And still gather honey for many a day.

Bonny bees, bonny bees, hear what I say!”

There was another example as late as 1892

My mother, who passed much of her youth in the village of Bakewell in Northamptonshire, tells me that the belief in the necessity of telling the bees everything was very strong there. At the death of a sister of hers, some of the cake and wine which was served to the mourners at the funeral was placed inside each hive, in addition to the crape put upon each. At her own wedding in 1849 a small piece of wedding-cake was put into each hive.

Folklore, Edition III, 1892, p. 138

Although this belief received a lot of news coverage in 2022 due to the Royal Beekeeper informing the Royal bees that Queen Elizabeth II had passed away. This idea of telling bees of a death to prevent them swarming is also found in northern France and the Channel Islands. In Picardy, Artois, the person who informs the bees taps the hive thrice; in Guernsey this is done with the key of the house, and if the bees answer with a hum, it is understood that they will remain and work for their new master.

In Normandy the death of any member of the family is announced thus: your father, mother, brother, sister, uncle, and so on, is dead. It is noteworthy that the dead person is always referred to as a relative of the bees. The hives were usually draped in black, but in La Vendee a black ribbon was only put on for the master or mistress.

Sometimes one of the dead man’s garments was buried in front of the hives before the funeral took place. In Mayenne a piece of the beekeeper’s linen, the dirtiest which can be found, was fastened to each hive, so the bees would then think he is there and so will not be tempted to follow him. In the Val d’Ajol, in order to prevent the bees from following their late master, the people put a piece of consecrated wax in each hive. In the Côtes-du-Nord the hives wear mourning for six months, and during that time the bees are said not to hum. In other parts the black remains on the hives for three weeks or forty days.

I know I usually examine a food in connection to the story, history and folklore but in this instance I really want to take the connection between bees and death folklore further by considering the role honey plays in the folklore of death and the afterlife. If you wish to just to explore honey and its role in historical food I have an earlier podcast and post which may interest you.

I think we will start, as so many things do, with the Egyptians and the Pharaohs. Honey was one of the grave gifts that was buried with Egyptian royalty as they considered honey an eternal food to be left forever in the sealed tombs, so that the dead might be nourished in the afterlife with honey in its natural state as well as in the form of honey cakes. Honey does not spoil so it was associated with immortality and resurrection.

A jar of honey was found, still in a fairly liquid state in the excavated tomb of King Tut. As far as could be determined the jar had been hermetically sealed and placed in the tomb some 3300 years before its discovery. Archeologists tasted the honey and found it to still be sweet and had identifiably honey flavours. It wasn’t just a grave good either, bandages were soaked in a liquid containing honey before wrapping the dead as its anti-bacterial properties retarded decay.

It wasn’t just the ancient Egyptians that venerated honey. The ancient Romans often used it to pay taxes and they loved it so much (well Virgil specifically) but were so mystified by where it came from that they considered that it might be sweat from the sky or spit from stars!

The miraculous status of honey may be why so many rulers and leaders (fictional and non-fictional) from the ancient world requested to be buried in honey. Either that or they thought that as honey was ‘incorruptible’ their bodies would not change or decay. Achilles, after being shot by an arrow in his only vulnerable spot, as well as the Kings of Sparta and Alexander the Great were all buried in honey. It wasn’t just people opting for this themselves. Herod I, King of Judea had his incredibly beautiful wife Mariamne executed as a result of a complex series of plots against her, which mostly originated from Herod’s wish for her to be executed in the event of his death as he didn’t want her to have another husband after him. Mariamne was not impressed by this and thus a series of actions occurred which led to her death. Herod had her preserved in honey and kept her by him for 7 years because he grieved her passing so much.

In Burma the bodies of important men were placed in honey for a year, because the preparations for the funeral took that time. A Burmese student in Manchester in 1925 reported that this custom was still in place but only for monks. Apparently the leftover honey was then sold at markets because it was considered incorruptible so that even the presence of the dead could not change its nature.

There was also apparently a recipe to make healing honey:

“Take one man-child and raise him up well-fed on fruits.

When he is about 30 years old, put him into a crock hewn of a single stone and sprinkle him with herbs and spices. Then fill the crock to the very top with honey and seal it tight for at least 100 years.”

The resulting honey would cure any illness. It is unknown whether this was a real practice but considered highly unlikely. Probably best to keep the idea away from any billionaires though, it’s the sort of think that might inspire them.

Honey wasn’t only used for burial and embalming or even snacks in the afterlife but was also used to honour, appease and make contact with the dead. The offering of honey to the dead is a very ancient custom. It seems that earlier civilisations thought that either they needed to regain the favour of the spirits of the dead or that they needed to be placated. Honey being the sweetest food known at that time was perfect to sweeten the relationship with those that had died.

The sacrifices to the dead were generally threefold, and usually consisted of honey, oil, and wine; or honey and milk or water, oil, and wine; but whatever the constituents were, honey was always one of them. There is even an inscription on a golden plaque, found in southern Italy, which reads: “The dead is thrice offered a drink; a honey-mixture, milk and water.”

In the Lucian’s Charon, Hermes is even asked why men dig a trench and burn expensive feasts and pour wine and honey into a trench. Hermes answered that he cannot think what good it can do them, but

“anyhow, people believe that the dead are summoned up from below to the feast, and that they flutter round the smoke and drink the honey draught from the trench.

In both the classical texts Iliad and Odyssey there are examples of the use of honey to attract the dead to receive their wisdom. Odysseus wants to call up the spirit of the seer Tiresias, and the enchantress, Circe, tells him first to dig a trench and make a sacrifice to all the dead:

“So, hero, draw nigh thereto, as I command thee, and dig a trench as it were a cubit in length and breadth, and about it pour a drink offering to all the dead; first with mead, and thereafter with sweet wine, and with the third time with water, and sprinkle white meal thereon; and entreat with many prayers the strengthless heads of the dead.”

Later, in Roman times, Silius Italicus in his 17 book poem Punica, tells how Scipio, wanting to call up his father’s ghost, went to Apollo’s priestess and recieved the following advice:

‘And therefore to Autinoë (who then

Under Apollo’s name the sacred Den And tripod kept), he goes, and open lays The counsels of his troubled heart, and prays To see his father’s face. Without delay,

The Prophetess commands him straight to slay, To the shades below, the usual sacrifice,

Two coal black lambs . ..

… Likewise joyn

To them choice Hony and purest Wine.’

Even the great playwright Euripides makes Helen send Hermione to the grave of Clytemnestra with offerings:

‘Take these offerings in thy hands. Soon as thou reachest Clytemnestra’s tomb, pour mingled streams of honey, milk, and wine.’

There is also a strong connection between honey and the Ancient Greek Underworld. A clear example is heard from Medea in the eponymous piece where she tells Jason to win the favour of Hecate by ”pouring from a goblet the hive-stored labour of bees” He learns from this and on another occasion he pours into the river sacrifices of honey and pure oil to earth, and to the gods of the country, and to the souls of heroes, beseeching them to aid him.

Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guarded the entrance to Hades, was known to be particularly fond of honey and was outwitted on more than one occasion by being thrown honey cakes. In the Aeneid a cake of honey and wheat is given to Aeneas by the Sibyl in order to placate Cerberus. This gift of honey cakes is believed to be a possible origin of the phrase, “A sop to Cerberus.”

One last thing before I share our recipe: did you know that at the dawn of the Christian era Britain was said to be a paradise of honey bees and inhabitants of the British Isles gained a reputation for longevity? The idea that beekeepers had very long lives persisted but the record may belong to an English beekeeper named Thomas Paar. He is said to have lived a quiet life in the countryside, drunk lots of honey wine, and eaten little, thus surviving to the age of 152. Then, in the year 1635, this remarkable man came to the attention of King Charles 1, who invited him to a feast in London to honour his great age. Unfortunately he ate too much at the feast in his honour and promptly died.

There is now just the matter of our recipe and I think this very simple recipe is perfect. Considering that we have been looking at some of the darker aspects of honey folklore it seems right that we should give gorgeous sweet honey a little sting in its tail in the form of chilli. It has a perfect balance of sweet and hot and is a fantastic addition to a cheese or charcuterie board. My favourite use of it is drizzled over a home-made, thin crust margarita pizza topped, once out of the oven, with scattered rocket, crumbled tangy white goat’s cheese and plenty of salty prosciutto.

Hot Honey

10

servings20

minutes15

minutesIngredients

250ml runny honey

2 tablespoons of dried chilli flakes

1tsp of apple cider vinegar

Directions

- Add the honey and dried chilli flakes to a saucepan. Heat over medium heat until the honey very lightly begins to simmer. Give the mixture a quick stir to combine, then remove pan from the heat.

- Let the mixture rest for 10 to 15 minutes

- Give the honey a quick taste to test the heat level. If you would like a spicier honey, add more chilli flakes and/or let the mixture continue to infuse for longer.

- Strain. Once the honey has reached your desired heat level, strain the honey through a fine mesh strainer into a clean storage jar. Stir in the apple cider vinegar until evenly combined.

- You can use straight away or let it cool to room temperature & place a lid on the jar and store at room temperature for up to 3 months.

Notes

- This is best with dried chillis, if you do decide to use fresh ones then the resulting honey must be stored in the fridge for a maximum of 1 week

- Photo by Arwin Neil Baichoo on Unsplash

Further Reading

Thistle & Thyme – Sorche Nic Leodhas

A Taste of Honey – Jane Charlton & Jane Newdick

The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore

The Honey Book – Emily Thacker

The Book of Honey – Claude Francis & Fernandez Gontier

The Magic of Honey – Dorothy Perlman

The Honey Book – Lucille Recht Penner

Shropshire Folklore Volumes 1-3 Charlotte Sophia Burne

Telling the Bees & Other Customs – Mark Norman

County Folklore, vol. v, Lincolnshire, 1908

Folklore, Edition III, 1892, p. 138

Murphy, Luke & Ameen, Carly. (2020). The Shifting Baselines of the British Hare Goddess. Open Archaeology. 6. 214-235. 10.1515/opar-2020-0109.

Jan Wall (1993) The Witch as Hare or the Witch’s Hare: Popular Legends and Beliefs in Nordic Tradition, Folklore, 104:1-2, 67-76, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.1993.9715854

https://www.terriwindling.com/blog/2015/10/mythic-hares.html

Featured Image Credit: mage Credit: Robert Gillmor, The Running of the Hare, 1992, colour linocut on paper,