In which we discover that even in the darkest of tales we can find some light, that boldness & curiosity can save lives, and that a pie can hold both wonders and terrors.

In which we discover that even in the darkest of tales we can find some light, that boldness & curiosity can save lives, and that a pie can hold both wonders and terrors.

The tales in this episode are traditional tales but contain some dark & violent themes.

The tales in this tale are Mr Fox, Captain Murderer and The Rose-Tree

The episode recipe is Leek, Cheese & Potato Pasties

If you would like to find more information about any of the stories, books or research mentioned in this episode you can find them in Further Reading.

You can also find out more at Hestia’s Kitchen which has all past episodes and the connected recipes on the blog. If you’d like to get in touch about the podcast you can find me on Twitter or Instagram at @FairyTalesFood.

Drawn to Darkness

I’ll just apologise now for all the darkness, death and goriness but I was strangely drawn to these stories and wanted to look into what the themes really meant. I should probably have waited for when the year turns again. They may not be the best tales for when the world, in this hemisphere at least, is showing everyone how beautiful & light she can be. At least one of them had a nearly happy ending and the perpetrators of the crimes in all three tales came to a bad end.

You know Chesterton said about fairytales: ‘Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon’

We definitely needed that St George here because these crimes are truly evil. We can’t say that we’re over-reacting and looking back through a modern lens, serial murder, cannibalism and child murder were as unforgivable then as they are now. So we need to ask ourselves why these tales (except for Captain Murderer) were still appearing in collections for children in the late 19th Century.

I suppose because they are cautionary tales, they teach that you should beware of strangers no matter how rich and charming they appear. They also reinforce, in the case of the Rose Tree, the very victorian patriachal view that many women aren’t to be trusted.

Where have I seen you before?

They are very different tales though so we should probably look at them separately. Let’s start as we began with our tales and take a look at Mr Fox. There are variations of this tale in Joseph Jacobs’ English Fairy Tales as well as in English Fairy Tales retold by Flora Annie Steel. The idea of a maiden visiting her betrothed and finding him to be a villain crops up again in the Oxford Student, The Cellar of Blood, Mr Fox’s Courtship and the Brave Maidservant. The Robber Bridegroom as retold by the Brothers Grimm in 1812 also has a lot of similarities. The tale of Mr Fox is much older than that however. A phrase in Much Ado About Nothing from circa 1599 references it directly:

‘Like the old tale, my lord: “it is not so, nor `t was not so; but, indeed, God forbid it should be so.”’ (Act 1, Scene 1). If it was considered an old tale in 1599 then it definitely has some antiquity. There are also references to the ‘Be bold’ phrases in Spenser’s The Faerie Queen from 1596 so it suggests that the Shakespeare reference isn’t just a coincidence and that the full tale formed part of the English oral tradition in the 16th century if not before.

The tale is categorised as ATU 955 The Robber Bridegroom but as I’ve just mentioned it is very possible that the English version predates both the German tale and the French tale Bluebeard which shares a lot of similar points of reference.

Brave and Bold

I loved the fact that Lady Mary, although she had fallen for our charming villain was not prepared to take everything at face value. I’m sure she didn’t expect to see the horrors that were secreted in Mr Fox’s property but she clearly wanted to make sure she was getting the deal she thought she was getting and not buying a pig in a poke. Marriage was much more of a business proposal back then as demonstrated by the pubic signing of the contract. She perhaps thought his home and fortune weren’t as big as promised and she wanted to check before it was too late to back out.

She was very brave when she found Mr Fox’s hidden horrors and clearly had a strong stomach to be carrying round a cold, dead hand. Just a quick aside here, in some versions the hand is encumbered by a richly jewelled bracelet but it has always seemed that the ring on the finger is far more likely, just for practical reasons. I admired the fact that she probably realised that as a woman she wouldn’t necessarily be a credible witness against a rich man so she took along the hand for proof. I also liked the fact that she was rewarded for her boldness and curiosity, a less than usual outcome for a folktale and in direct opposition to the tale of Bluebeard.

Sacrifice & Revenge

So Lady Mary triumphed and I wish that was the outcome of our second story too for our second clever girl but I suppose we can at least say she got her revenge. This story was apparently a folk tale told to Charles Dickens by a maid when he was a child in order to scare him. Although there are quite a few points of reference between our first two tales they differ on two big points. Firstly Captain Murderer actually wants to kill and eat his victims although he might not be averse to taking any valuables they might have, that is not his main aim. Secondly our clever, bold girl is neither rescued or manages to escape but the whole point of her incredibly brave plan is that she knows she won’t and goes through with it just to extract a post mortem revenge for herself and her sister. I think it might be closer to Three Sisters that Marry the Devil, but at least that story has a happy ending through the youngest clever sister outwitting the devil and managing to save her elder sisters.

Jealousy

So to our third tale linked to the last by the eating of an innocent in a pie or pasty at least but here the motivations are completely different although they might actually be crueller. The cannibalism in this tale is all about female jealousy of by an older woman for a young and beautiful girl. This slightly different to other tales such as Snow White where the evil queen wants to consume Snow White’s internal organs to absorb her youth & beauty. In the instance of our tale the stepmother wants her husband and son to consume her stepdaughter to redirect their love for the child back to her.

She is almost driven mad by the jealousy that the love her stepdaughter more than her. Apart from the fact that the step daughter is the one that dies, you might recognise the plot as that of The Juniper Tree but even more sad. I don’t know which came first or even if there is a true variant. It may just be an adaptation of the Juniper Tree to fit a certain set of circumstances but at least the ending of this is sadly beautiful even if the guardian spirit of the tree was not there to save either child. The wicked stepmother at least did not get away with her evil deeds just like in the worrying number of tales where parents are fed their own children in revenge. If you really want to know they are mostly Greek and I can send you a list if get in touch.

Worst Pies in London

I am going to a bit ghoulish though in my choice of food for today’s episode which is pie. You’d guessed already hadn’t you, I know its a dark connection but I couldn’t help myself. I think it was being told the story of Sweeney Todd at too young an age and then it being reinforced by hearing the catchy tune in the film musical of the story: ’The Worst Pies in London’ Pie does have some other ghoulish connections including in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus which takes advantage of our primal fear and terrible fascination of the possibility of being fed human flesh unknowingly. Pie particularly lends itself to this because the inside of a pie is a hidden thing and its filling is unknown.

Magpies & Other Etymologies

Its actually possibly how it got its name, not the unwitting cannibalism, but the large number and combinations of possibly fillings. The Oxford English Dictional suggests that the etymology is the same as that of magpie as they collect a miscellany of things for their nests and so do pies. Not that pies have nests but you know what I mean. Their first mention is in 1304 so pies have a long history. If you define a pie as something wrapped in dough then a lot of early food would be considered pie as it was really the only way to bake things in a bread oven and retain any moisture when cast iron casserole dishes with lids had’t been invented.

The dough was vey thick and often hard through long baking and meant to be up to preserving the contents from interacting with the air sometimes for months. These were known as coffins and although it is the generally accepted wisdom that these weren’t eaten it is unlikely they would let any food go to waste at that time and there are recipes that use them crumbled to thicken sauces and it possible other leftovers would have gone to the lowliest of servants to eat.

Just Add Fat

What changed was when fat was added to flour and water dough and it became pastry. There is a suggestion that there is even an early reference to puff pastry in The Forme of Cury. Going forward from there are lots of references to what pastry should be used with which dishes and some include instructions to make the pastry ‘tender’ which wouldn’t have been needed if crusts weren’t going to be eaten.

There were still the tough crusts for items that were meant for preserving food but other crusts formed part of the meal. Fine wheat flour and butter and sometimes cream were considered to make the best crusts. Although in Britain lard was used in hot water pastry which enabled high sided and fairly structural pie cases to be made. Pork pies are still made in this way today.

Fuss About Filo

Im just going to stress here that I’m talking about Western Europe here. Filo pastry is almost certainly older than the pastry I mention here but it makes a very different product to the pies I discuss here. I love filo and other similar thin pastries and revere the skill involved in making them but they wouldn’t work to protect a big haunch of venison from rot for example unless it was just to make it so delicious that you ate it all before it could go off.

High Status Deer

Speaking of venison it was considered to make the best pasties and Samuel Pepys referenced them several times in his diaries. I had visions of the size pastries we see today but they were actually huge with whole joints of venison inside with enough feed a dinner party. Venison was the status meat of the time, you could only get it if you hunted on your own land, were given permission by the king to hunt on his land or were given it as a gift by a landowner.

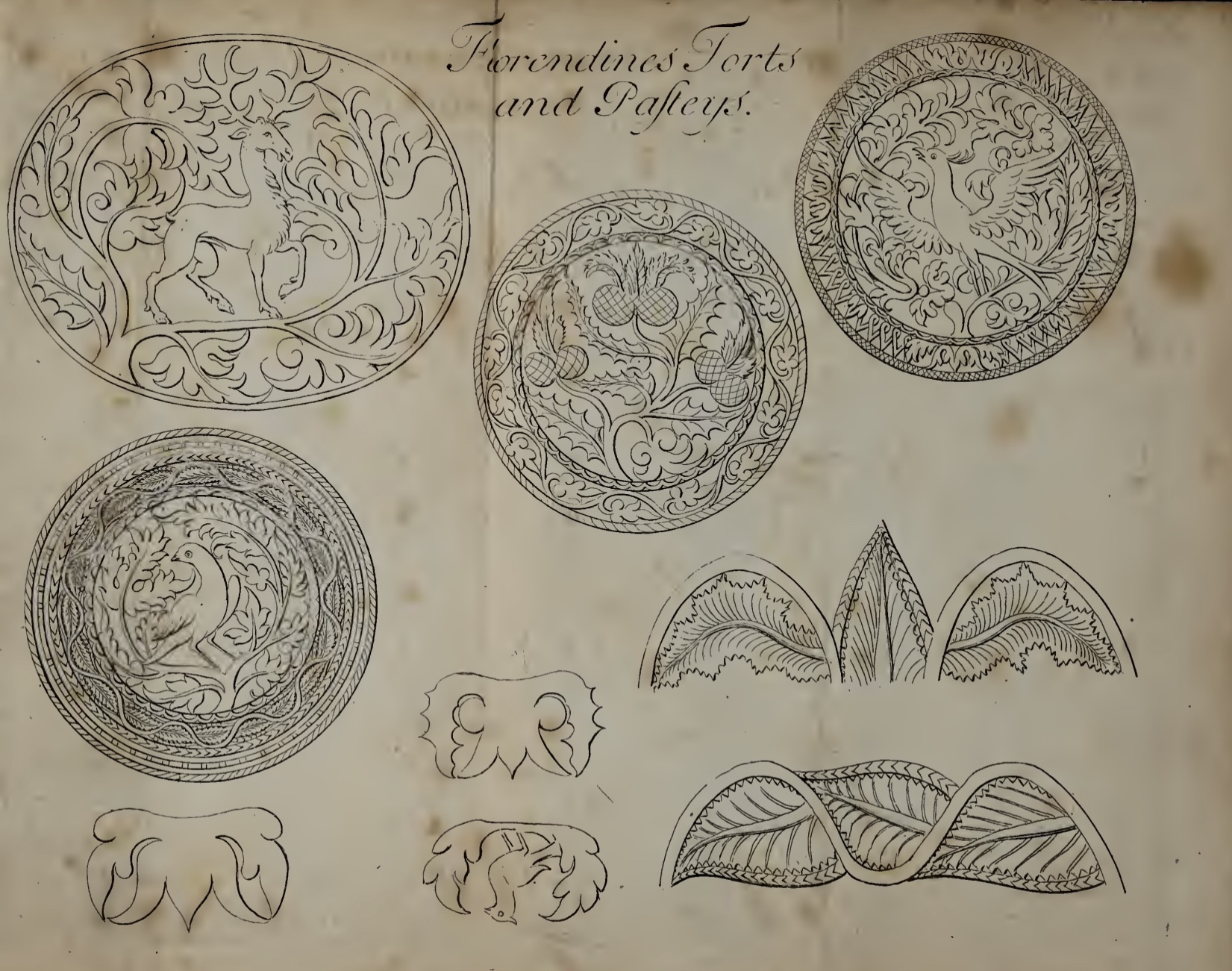

There are even recipes for cooks to disguise lesser meats such as beef with herbs that dyed the meat a darker colour to give the impression of venison. There were even books with special pastry designs for your venison pasty, so that people would know how special it was.

Cornish Pasties

They were nothing like the Cornish pasties of today with beef and vegetables. The love of these convenient foodstuffs is considered to be particularly British and it is true there many flavours out there and places on every high street that sell them. I’m a fan of a cheese, onion & potato one myself even though a true Cornish person wouldn’t recognise that as a proper traditional filling. I grew up part of my life in Devon though and don’t have to listen to people that insist on putting their cream and jam on scones in the wrong order. Cornish pasties with their thick crust on one side of the pasty though were specially designed as a working lunch though, excellent for carrying down tin mines and being eaten with grubby fingers as the thick handle need not be eaten.

North Michigan Pasties

I have discovered though that the British are not the only ones that love their pasties. There is a community in Northern Michigan in a area known as the Upper Peninsula where they share our love for this convenient food. It comes from Cornish tin miners who emigrated there to work the tin mines. When miners from other countries, in particular Finland, joined the community they copied the foodstuff as it was obviously a good food for the job. The pasty has been adapted but is still recognisable as the functional foodstuff we know and love although most have lost their Cornish Crimp as a way of holding the dough together.

The community was pretty much cut off from the rest of Michigan until 1957 when a bridge was built which made travelling there much more convenient which meant the pasty was left mostly undisturbed. Now pasties are a tourist attraction and some shops are famous for their specific pasty and people make special journeys. Its a wonderful example of how foods migrate and I’ve included a really interesting paper from the proceedings of The Oxford Food Symposium from 1983 that examines this in great detail in Further Reading.

Rhymes & Ridiculous Theories

I bet you thought I’d got carried away with pasties and forgotten the folklore but I haven’t. There is so much attached to lots of local ones that I could write an episode just on those. I don’t want to leave any out so I though I’d concentrate on the folklore of pies in three nursery rhymes: Little Jack Horner, Georgie Porgie, and Sing a Song of Sixpence.

Little Jack Horner

Sat in the corner,

Eating his Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

And said, “What a good boy am I!”

This rhyme has been used by politicians of all sides to mock the opposition. It is first referenced in 1725 but the folklore is in the tale that suggests the origin of the rhyme Iies with Thomas Horner, who was steward to Richard Whiting, the last abbot of Glastonbury before the dissolution of the monasteries. It is suggested that, prior to the abbey’s destruction, the abbot sent Horner to London with a huge Christmas pie which had the deeds to a dozen manors hidden within it as a gift to try to convince the King not to break up Church lands. During the journey Horner opened the pie and stole the deeds of the manor of Mells in Somerset. It is also said that, since the property included lead mines that the plum is a terrible pun on the Latin plumbum, for lead. Thomas Horner did actually became the owner of the manor, but subsequent owners of Mells Manor have insisted that the legend and folklore are untrue and that Wells purchased the deed from the King.

Georgie Porgie

Georgie Porgie, pudding and pie,

Kissed the girls and made them cry,

When the girls came out to play,

Georgie Porgie ran away.

You can take your pick here of the lore behind the rhyme. The most popular is that it was about George, Prince Regent who seriously loved his food, was known to press his unwelcome attentions on young women. He also made his wife and mistress extremely unhappy. He also had a reputation for making a quick getaway from illegal prize fights. An alternative is about George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham but it takes some stretching so I’ll let you look it up yourself.

Sing A Song of Sixpence

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye.

Four and twenty blackbirds,

Baked in a pie.

When the pie was opened,

The birds began to sing.

Wasn’t that a dainty dish

To set before the king?

The king was in his counting house,

Counting out his money.

The queen was in the parlour,

Eating bread and honey.

The maid was in the garden,

Hanging out the clothes,

When down came a blackbird,

And pecked off her nose.

This one has many alternative solutions. It is possible that the origins of the story go back as far as 1454. A feast in was held in Lille by Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good to gain support for a crusade, and one of the entertainments was a giant pie containing a group of musicians who ‘sang’ when the pie was opened. Another alternative, the rhyme may be about the day – 24 birds representing the hours, the opening of the pie and the singing of the birds referring to the dawn. Some suggest it is about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and that Anne made the pie to entrance Henry. There are actual various contemporary instructions for making pies where livestock jumped out upon opening which were very popular in the Middle Ages. The least likely suggestion is that it is a coded message for the recruiting of pirates by the famous Blackbeard, as some urban myths contest.

The folklore behind nursery rhymes is fascinating and I’d recommend you have a look into it if you get chance.

So all that’s left is a recipe and I’m sending you to my favourite recipe for pasties: https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/recipes/leek-cheese-potato-pasties but they are even better and quicker with ready rolled all butter puff pastry. These are delicious cold should you have any left over too. They are also vegetarian just in case the earlier disturbing subject matter has made you feel like converting.

Further Reading

Pie, A Global History – Janet Clarkson

https://www.foodtimeline.org/foodpies.html

Folk-Lore from Wales – Folklore , Sep. 30, 1919, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Sep. 30, 1919), pp. 238-239

‘Cannibal Tales – The Hunger For Conquest’ by Marina Warner.

The art of cookery refin’d and augmented: containing an abstract of some rare and rich unpublished receipts of cookery (1654), Joseph Cooper

The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Knight Opened(1669) – Kenelm Digby

The English Housewife (1664) – Gervase Markham

The Whole Body of Cookery Dissected (1673) – William Rabisha

Robert May’s The Accomplish’t Cook, or, The Art and Mystery of Cookery: Wherein the Whole Art is Revealed (1678)

Hannah Woolley’s The Queen-like Closet (1670).

The Oxford Companion to Food – Alan Davidson

E Kidder’s Receipts of Pastry and Cookery

The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales edited by Donald Haase

Food and Drink in Britain From the Stone Age to the 19th Century, C. Anne Wilson

Food in Motion, The Migration of Foodstuffs and Cookery Techniques – Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1983

- The Cornish Pasty in Northern Michigan by William G Lockwood and Yvonne R Lockwood

Wrapped & Stuffed Foods – Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012

- The Most Frugal of the Phyllo-wrapped Pies (or How to Feed a Crowd with a Handful of Meat) – Aglaia Kremez

- ‘Four and Twenty Blackbirds Baked in a Pie’: A History of Surprise Stuffings – David C. Sutton

- Samuel Pepys’s Venison Pasties – Taissa Csáky