In which we discover that fate can be tricksy, fish pie can be surprising and that you can get away with pretty much anything if you are a baron.

In which we discover that fate can be tricksy, fish pie can be surprising and that you can get away with pretty much anything if you are a baron.

This episode includes a wonderful story about fate, the history of fish pie and a fantastic luxury pie recipe.

The link for today’s recipe is here

If you are interested in the faithless queen you can read about her in the Life of Vertigern

If you are more interested in Polycrates then you need Herodotus

You can find the links to the historic cookbooks I mentioned on my blog.

This is the shortest story I have told so far, and it appears to be a simple tale. There is however, a longer and more complex story behind the folklore.

Dating this particular tale

The story was first collected in print in 1866 by William Henderson in Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders. It then appeared in Joseph Jacob’s collection English Folktales in 1890. There are some very specific elements of the tale which would seem to date its first telling. Barons did not exist (not with that title) until after the Norman invasion in 1066. Although Scarborough Castle has a very long history, there was only really one period after 1066 where it could be considered to be private residence and that is between 1308-48.

Henry, Lord Percy (previously Baron de Percy) lived there during that time and he had a brother also in Yorkshire and there is some mystery why he did not inherit. I would never libel an unknown Baron (William de Percy) but maybe the rumours of his apparent magical abilities are at the root of his disgrace. I have used his name William in my story for an added frisson.

Even more historic origins

The origins of the story are somewhat older than this telling. It is a story of two parts: before and after the marriage. The first part is very similar to several European folk tales (Hungarian, Swedish, German) and a Mongolian tale. The English version is the only one where the poor child is female.

The German story (The Devil with the Three Golden Hairs) is the one that most closely resembles the English tale with a King taking the place of the Baron. The letter changeover by the thieves is the same. The second part of the English story is where it demonstrates its age. The root of this part can be seen as far back as the story of Polycrates as told by Herodotus. Herodotus died in roughly 425BCE so that’s some history. There are also similar versions in 1001 Nights.

Mystical Plot Devices

It is also suggested that there is a mystical significance to this plot device. The ring descends into darkness and is brought back into light symbolising the sun’s overnight journey. It would be quite a stretch to link that to the English version so I’ll just leave that there. I don’t think this story is linked to the Norwegian story of The Ring in the Fish which highlights the perils of tempting fate. The English tale is clearly demonstrating that you can’t change your fate.

It is also possible that the device of discovering a ring in a fish was influenced by the tale of the faithless Queen Languueth in the Life of Kentigern. There is a link in the Further Reading to a translation of this manuscript as well as the section of Herodotus if you can’t stand the suspense of not knowing what happens in these tales.

Actual Cooking

You might have noticed that there was actual cooking in this tale! I do slightly resent the fact that everyone was so amazed that a great cook could be young and beautiful. Aelis did also seem to be promoted fairly swiftly from scullery maid to cook but perhaps the labour market was faster moving in those days.

The coastal location of the story is key to the fish being served. Medieval inland dwellers would not have eaten much fresh fish if at all as fish spoils so quickly. They would have eaten dried salt fish though, supplemented with river fish. The church had many fast days (at least 3 a week) where meat was forbidden so fish was the only option.

That is if you don’t stretch your definition of fish to include dolphins, puffins, porpoise, beaver’s tales and barnacle geese. Its one of the reasons that Beavers became extinct in the British Isles, the others are the market for their fur and castoreum. The last beaver on these islands was shot in 1526 and they weren’t reintroduced until 2011. Don’t even ask about the barnacle geese.

Back to Fish

We must not get side-tracked by beavers, and geese, barnacled or otherwise. We have more important things to concentrate on. Fish pie is the subject for our interrogation this week. I tried looking at just a perfect baked fish but in all honesty not much has changed since medieval times. We just don’t overcook it as much now.

Fish pie, on the other hand, has changed dramatically. This research took me more time than everything else in this blog even if you count reading the Life of Kentigern. Sadly it will can be summed up in several sentences so I’m going to illustrate it with some original recipe pictures just to demonstrate my commitment to food history.

The only similarity that medieval fish pie and the one we consider the be the current definitive version share is fish. It isn’t even the same fish really. As discussed most inland dwellers only had access to river fish or preserved fish so most of the early recipes are for eel or herring (the oily flesh made it good for pickling).

Fish Pie Surprise

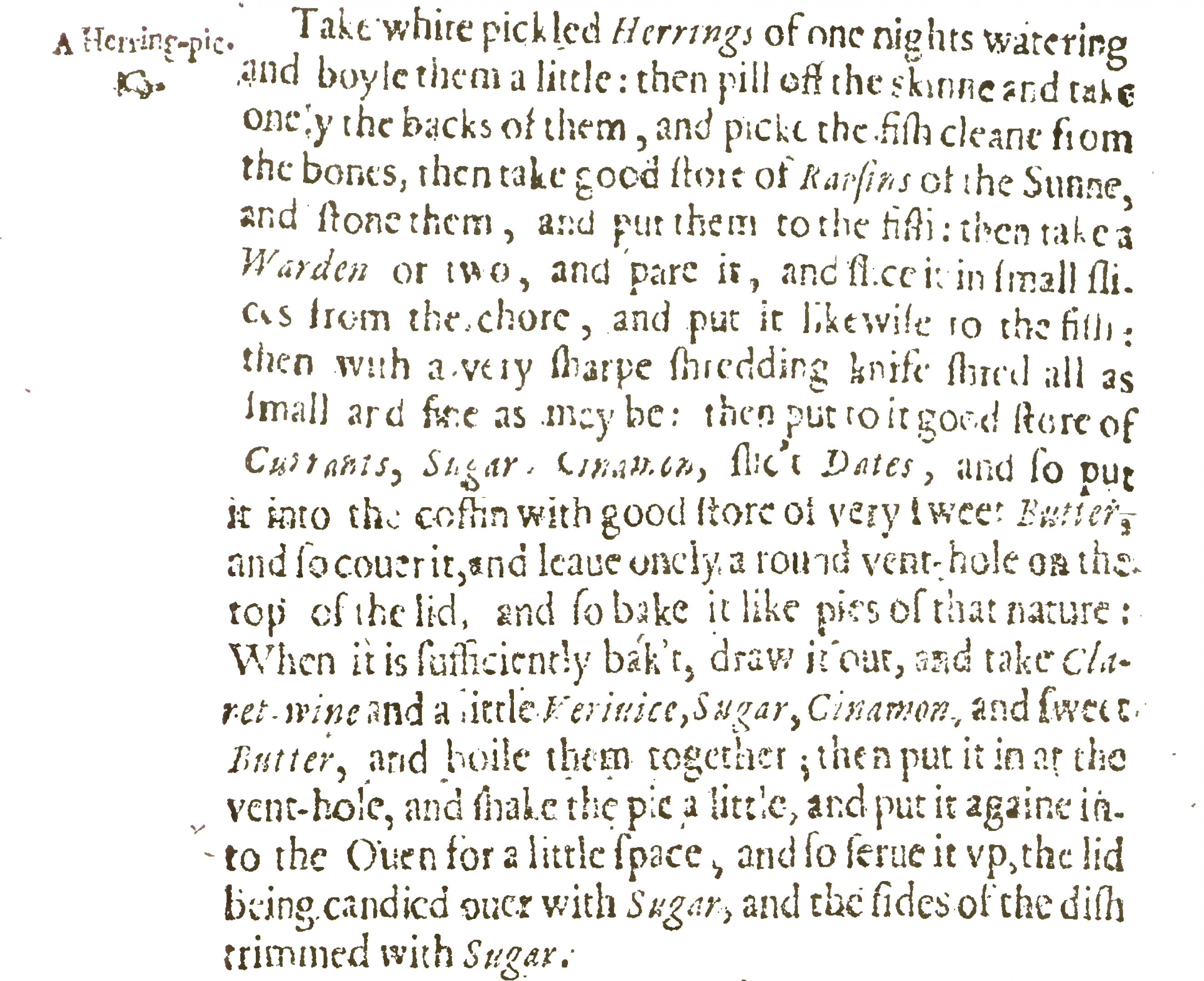

This recipe from 1631 (I know that’s not medieval but this was the earliest recipe I could access) has a pastry coffin (possibly not meant to be eaten ), pickled herrings, sliced pears (warden) raisins, currants, cinnamon, sugar, dates, and is finished afterwards with a finishing liquid of boiled claret, verjuice, sugar, cinnamon and butter.

If you ignore the pastry it has a lot in common with the Venetian dish Sarde in Saor which came about as a way of preserving fish on board sailing vessels which travelled between Venice and the Far East utilising spices that they had on board as well as vinegar and honey.

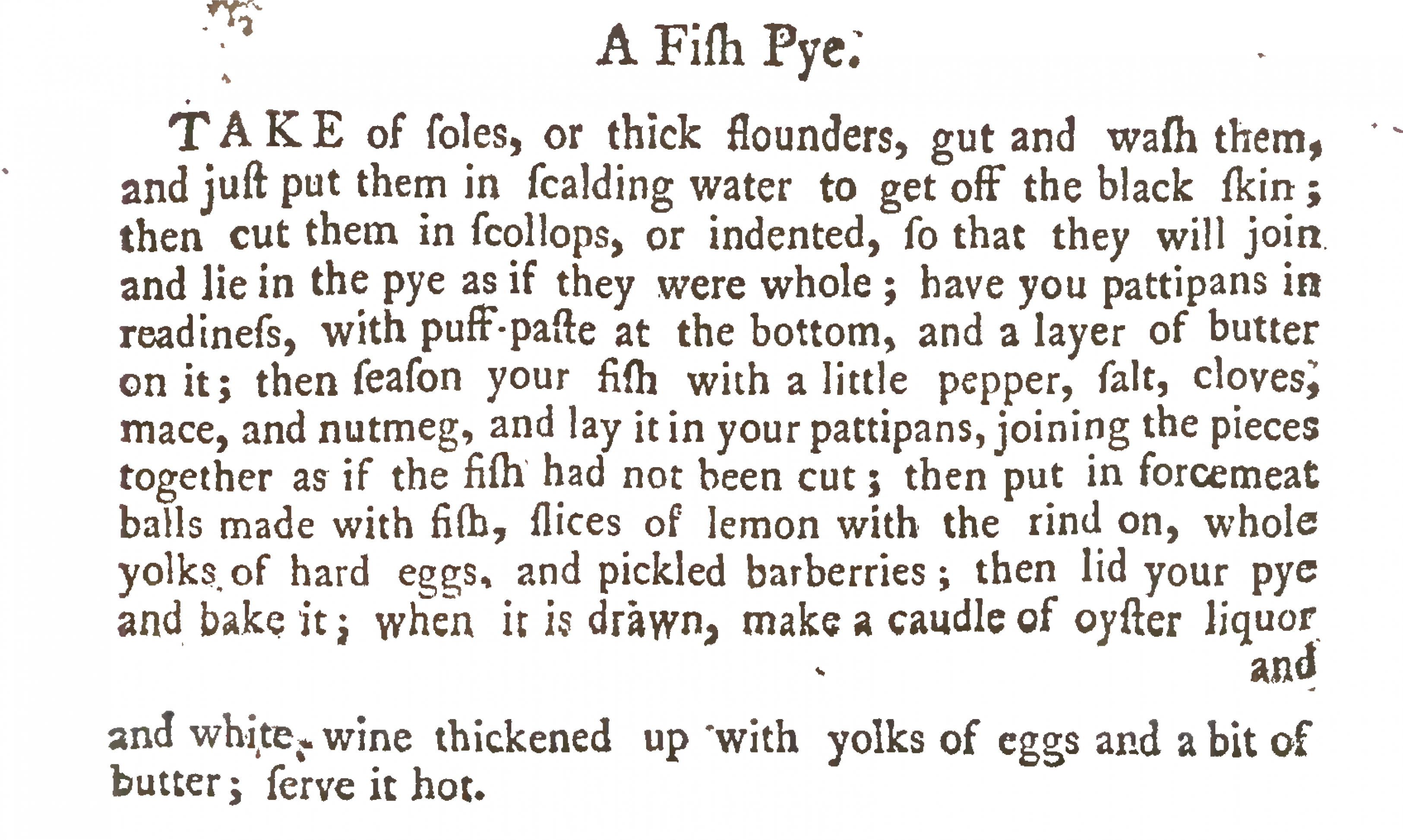

The first mention of Fish Pie as oppose to recipes for specific fish was in 1725, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. I have a recipe here from The Compleat Cook in 1773 (its also the same in the 1734 edition but its not so clear to read). We have lost the inedible coffin and replaced it with puff pastry, the pears, sugar and other dried fruits have also disappeared (although we do have pickled barberries). The fish is no longer pickled and we now have boiled egg yolks, lemon slices and forcemeat (stuffing) balls made from the fish trimmings, . The spices have remained but the oyster liquor & white wine thickened with eggs and butter to be poured in after baking is much more to modern tastes. A lot has changed in just over a hundred years.

Pastry

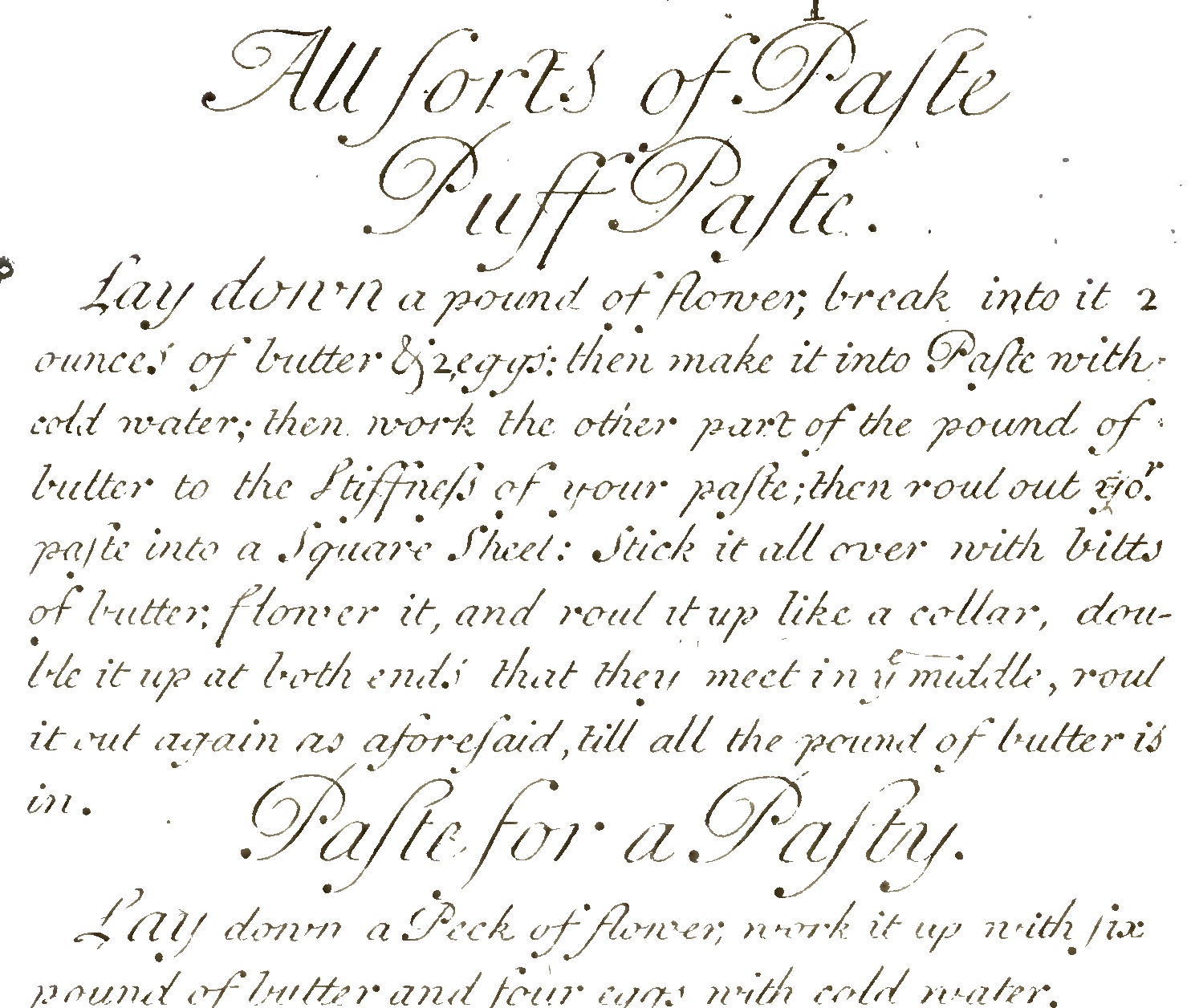

I feel we should have an honourable mention for the pastry, plus this book, E. Kidder’s receipts of pastry and cookery, from 1720 is so beautiful I couldn’t help sharing. Pastry had also come a long way from the hard container that was the medieval equivalent of Tupperware.

Ok, when did things start to change?

We start to see fish being cooked with béchamel around the middle of the 19th Century and then examples of fish, fish gravy and pastry towards the end of the century. In 1895 there is a recipe in Mrs. Wilkinson’s Cookery Book for fish pie containing fish mixed with béchamel sauce and topped with breadcrumbs. In Plain Cookery Recipes, as taught in the school also from 1895 there is the first mention that I could find of a mashed potato topping.

Then finally in 1907 in the Polytechnic Cookery Book, I found a recipe which is very similar to the standard definition of a modern fish pie with mixed fish, béchamel style sauce, boiled eggs and mashed potato topping. Its not clear when smoked fish started to be added. I suspect that it might have been during the war when fish wasn’t rationed. Smoked fish had a much stronger shelf life which improved availability. Potatoes also weren’t rationed so this might have been the point that it became the most popular topping. A lot of this conjecture because it is harder for me to track changes as many cookbooks from this period are still in copyright and haven’t been digitised.

Finally the recipe

I’ve brought us pretty much up to date, the recipe hasn’t really changed much since then. There have been some luxury additions like king prawns or scallops and maybe cheese in the mash or the sauce. (Unlike in Italy we are very happy to have fish and cheese at the same time). There are also those changes people have made to make the pie less rich but essentially we are making the 1907 recipe with knobs on.

Fish Pie Surprise

4-6

servings1

hour20

minutesThere isn’t really a surprise, unless you think eggs or prawns are surprising. I suppose the leeks in the mash might count. Anyway its lovely, rich and cheesy with delicious fish. You don’t need much with this. A big pile of peas would be perfect or maybe steamed broccoli or even both, green things anyway.

Ingredients

- For the cheesy leek mash

1 kg (3-4 large) floury potatoes, such as Maris Piper, peeled and quartered

100ml milk

2 medium, free-range egg yolks

50g unsalted butter, softened

1 large leek, thinly sliced and washed well

75g Cheddar, coarsely grated

- For the fish

300ml milk

200ml double cream

250g firm white fish (see this list for the most up to date sustainable choice)

200g raw king prawns, cut in half

225g smoked haddock or smoked cod fillet

200g salmon fillet

- For the herb sauce

50g butter

3 tbsp plain flour

250ml chicken or vegetable stock

¼ tsp freshly grated nutmeg

Small bunch flat leaf parsley, chopped

Small bunch tarragon, chopped

- For the Pie

3 hard-boiled eggs, peeled and sliced horizontally

Directions

- Melt 50g butter in a small pan, add the sliced leek and cook gently for 3-4 minutes, until tender.

- Next the mash for the topping. Place the potatoes in a large pan of cold, salted water, bring to the boil and simmer for 20 minutes or until cooked through. Drain, then mince with a potato ricer or mash finely. Mix in the milk, followed by the egg yolks and buttery leek, then season and set aside.

- Preheat the oven to 180°C. Place the cream and milk mixture into a saucepan and bring to a very gentle simmer. Add the fish (except the prawns) and slowly poach for 5 minutes. Remove the fish, allowing it to cool slightly and flake into large chunks, and reserve the liquid.

- Make the herb sauce by melting the butter in a medium saucepan over a moderate heat. Whisk in the flour and cook for a couple of minutes. Add the reserved poaching liquid and whisk well. Stir in the stock, nutmeg and season to taste with salt and coarsely ground black pepper.

- Cook over a low heat, whisking until thickened, then remove from the heat, mix in the herbs and fold in the flaked cooked fish and the prawns.

- Pour the mixture gently into the base of a 2 litre shallow dish. Place the slices of egg across the fish mixture.

- Spoon the mash on top, smooth then rough up gently with a fork. Bake in the oven for 15-20 minutes, until golden brown and piping hot.

Notes

- Make sure your dish is big enough!

Further Reading

Notes on the Folk-lore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders. With an Appendix on Household Stories by S. Baring-Gould. William Henderson.

English Fairy Tales Joseph Jacobs,

The Devil with the Three Golden Hairs – Grimm

Jocelyn, a monk of Furness: The Life of Kentigern (Mungo)

The English Housewife – G Mareham 1631 . p110

Complete Housewife & Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion E Smith 18th edition 1773

E. Kidder’s Receipts of Pastry and Cookery 1720

The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digby Kt 1677

Cookery book ; and, General Axioms for Plain Cookery 1890