In which we discover why you should never pose as an oil salesman, what your salt consumption reveals about you and how a good bread recipe connects the two. We also learn, more importantly, that a clever, courageous, quick-thinking woman is what you really need to save the day and the treasure.

In which we discover why you should never pose as an oil salesman, what your salt consumption reveals about you and how a good bread recipe connects the two. We also learn, more importantly, that a clever, courageous, quick-thinking woman is what you really need to save the day and the treasure.

This is the recipe for the excellent loaf that is topped with salt, doesn’t require any kneading and can be on the table in under 2.5 hours. It might be a less than obvious connection but I hope you’ll forgive me if you make it. Its so tasty and chewy and has holes like the expensive, time-consuming ones you see on instagram. It goes with almost every type of cuisine, is brilliant with soup and cheese but you can also dip it in houmous without a concern in the world.

I can eat at least half, just dipped in good, grassy extra virgin olive and a little extra salt. Just add a big glass of slightly rough red wine and a good book and it might be the perfect evening. Its also great for guests except for any robber captains that have decided on your death as the ultimate vengeance. Then again, you just can’t suit everybody.

This is an excellent recipe for lavash

Further reading:

The Story is the Thing

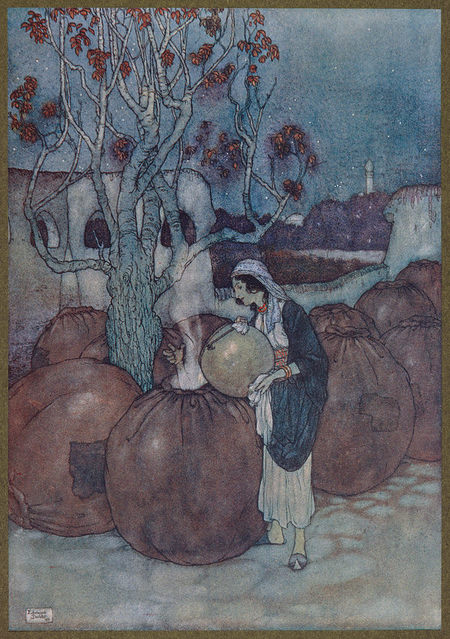

Everyone knows this story don’t they? Or at least a sanitised version. I think I must have been read the slightly less gruesome version because I knew I loved it because the heroine was clever. I didn’t ever think about bodies being quartered and hung up around the place or people being scalded to death with boiling oil. You’d have thought that would stick in the memory wouldn’t you?

I remembered the oil part but it didn’t seem so bad until I started reading lots of versions of the story to get a feel before my own telling. Its possible it just didn’t impact on me in the same way, although perhaps its as Terry Practchett says:

“But it was much earlier even than that when most people forgot that the very oldest stories are, sooner or later, about blood. Later on they took the blood out to make the stories more acceptable to children, or at least to the people who had to read them to children rather than the children themselves (who, on the whole, are quite keen on blood provided it’s being shed by the deserving*), and then wondered where the stories went. * That is to say, those who deserve to shed blood. Or possibly not. You never quite know with some kids.“

Whether that is true or not, I still love it because it is one of the rare wonder tales that values a woman for cleverness, not her beauty and willingness to get married. Without Marjana, it would be a very different story and certainly shorter. I have also developed quite a bit more sympathy for the robber captain than I had as a child.

World Literature?

I suppose on some levels you could consider 1001 Nights a piece of world literature due to its age and the number of retellings and explorations. However, as it is from outside my culture, I felt that in order to give it the respect it deserves I should do some more research.

Manuscript Editions

The Nights are made up of manuscripts that have recorded the oral tradition of the tales . There are two main Arabic manuscript traditions of the Nights, the Syrian tradition and the Egyptian tradition. The original text that Galland translated into French was a three-volume manuscript that has been agreed to date from the 14th or 15th Century and originated in Syria.

This tradition is also represented in print by the Calcutta edition and by the Leiden edition prepared by Muhsin Mahdi in 1984. This is considered to be the most faithful preparation of the linguistic style of the medieval Arabic currently available.

Texts of the Egyptian tradition contain more tales and are more varied but these appear later than the Syrian edition. Many more independent tales have been added to 1001 Nights over time, possibly to actually achieve the number in the title.

An Orphan Tale

Ali Baba and Aladdin are considered to be orphan tales as they are not from the original arabic text translated by Antoine Galland. They were told to Galland by a Maronite story-teller, called Hanna Diyab, who came from Aleppo in modern-day Syria. He told the story to Galland in Paris who wrote it down in French.

Diyab sadly received no credit but unlike with Aladdin, Galland seems to have at least treated his telling of Ali Baba in a more straight forward fashion. The story is much shorter and is told in a more direct manner. The action is faster and the dialogue more in keeping with the roles the characters play.

You shouldn’t have favourites but …

I think the best version, if you can get hold of it is The Arabian Nights: The Husain Haddawy Translation Based on the Text Edited by Muhsin Mahdi, Contexts, Criticism, ed. by Daniel Heller-Roazen. This contains Haddawy’s translation of the Leiden edition as well as four additional stories including Ali Baba and is considered to be the closest to the original. It also has an excellent commentary and several interesting essays.

Sheherazade (Who else?)

What all the texts have in common is Sheherazade. Her cleverness and resourcefulness are also reflected in Marjana’s character. I love critic Muneeza Shamsie’s quote:

“Sheherazade’s courage, intelligence and confidence and the fact that she succeeds, asserts the power of storytelling and imagination over that of tyranny and terror – a concept which has strongly influenced the ideals and ideas of our world.”

I could go on at length and the history of these tales and their translations is endlessly fascinating. There just isn’t space and I’m not a scholar. I’ve listed lots of good starting points for reading at the bottom of the blog if you’d like more information.

Cunning Culinary Connection

Now the bit you’ve all been waiting for, what dubious, tenuous connection can be made to a food and recipe? I may have given it away at the beginning but possibly no-one was paying attention. The cunning, culinary connection to this story is in the robber captain’s refusal to eat salt with Ali Baba when he plans to kill him.

There are lot of salt idioms in English, ‘below the salt’, ‘above the salt’, ‘to take one’s salt’. They come from a time when salt was an important and expensive item and how it signalled the status of the relationship between guest and host.

“Salt is so common, so easy to obtain, and so inexpensive that we have forgotten that from the beginning of civilization until about 100 years ago, salt was one of the most sought-after commodities in human history.”

Mark Kurlansky, Salt, A World History

Say It with Salt

There is a significant history to eating of salt or bread and salt in Arabic culture to cement relationships. Eating bread and salt with a friend is considered to create a moral obligation which requires gratitude. This is echoed in many other cultures across the globe, especially in Eastern Europe where it is an expression of hospitality to guests. Bread and salt are also significant in the culture of the Jewish diaspora and form part of the ceremony of Kiddush.

I have noticed that in several versions of the story Ali Baba tells the captain that his bread does not contain salt. I though this might have significance but after a lot of research I can’t find any special reason for this. It is difficult to make a yeasted bread (even a sourdough) without salt because it effects the chemistry and liquid levels as it competes with the yeasts for water.

The only suggestion I have is that this bread could have been an unleavened flat bread known as Lavash which is still popular all over the Middle East, Armenia and Georgia, and is believed to have its roots in present day Iran.

Recipes and A Confession

This is an excellent recipe for lavash. I haven’t given my own as I like to leave fantastic flatbreads to the experts. I must confess to buying my parathas and chapatis ready rolled and frozen and I order in my Khobz and Lavash.

I can however, turn my hand to an excellent loaf that is topped with salt, doesn’t require any kneading and can be on the table in under 2.5 hours. It might be a less than obvious connection but I hope you’ll forgive me if you make it. Its so tasty and chewy and has holes like the expensive, time-consuming ones you see on instagram. It goes with almost every type of cuisine, is brilliant with soup and cheese but you can also dip it in houmous without a concern in the world.

I can eat at least half, just dipped in good, grassy extra virgin olive and a little extra salt. Just add a big glass of slightly rough red wine and a good book and it might be the perfect evening. Its also great for guests except for any robber captains that have decided on your death as the ultimate vengeance. Then again, you just can’t suit everybody.

Fast No-Knead Loaf

An excellent loaf that is topped with flaked salt or other seeds/spices of your choice, doesn’t require any kneading and can be on the table in under 2.5 hours.

Ingredients

250 g bread flour

7 g instant dried yeast

230ml warm water

2 tsp sugar

1 tsp fine salt

1 tbsp olive oil, for glazing

Directions

- Mix the flour, sugar, salt and yeast in a large mixing bowl.

- Pour the water into the bowl and mix everything together. Do not be alarmed, it will be a wet, sticky mess which is exactly what you want.

- Cover the mixing bowl with a big plate or anything else that covers it and leave to prove for about one hour (or until it has doubled in size).

- Now you have a couple of options depending on your level of confidence: either

- Put the olive oil onto the tray and smear it about to cover a circle about 20cm diameter then with your olive oily hand pull the wet dough into a ball by taking the outside of the dough and tucking it into itself in a rough circle then scoop up and dollop onto the tray covering with the oil and then turn onto the tray with the nice smooth, side up or.

- Flour a work surface and tip the proven dough out on to the work surface making sure to add lots of flour to avoid sticking. Shape the dough into a flat circle (about 2-3 cm high) then place the dough on a olive oil-greased baking tray.

- Cover the dough with a tea towel and leave to prove for another 45 minutes. Preheat the oven to 250° in the last 20 minutes of this time.

- Then sprinkle with sea salt flakes or seeds or even za’atar, and gently press into the dough

- Bake the bread for 8 minutes at 250° C and then turn the oven down to 200° C and bake for another 5 minutes (or until golden brown).

Notes

- You could add olives or sun-dried tomatoes before the second prove if you fancy or any other combination you are partial to but watch out for adding too much extra liquid.

Further Reading

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/mar/12/arabian-nights-illustration

Salt, A World History by Mark Kurlansky

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bread_and_salt

Head over to my About Me page if you’d like to know a little more about me

Image Credit: Drawing by Edmund Dulac from Stories from the Arabian Nights, retold by Lawrence Houseman

Recipe image credit – Hestia’s Kitchen